What’s Up For June 2017?

What’s Up for June 2017?

Have a planet party and compare Saturn and Jupiter! We’ll show you where and when to point your telescope or binoculars to see these planets and their largest moons.

Meet at midnight to have a planetary party when Jupiter and Saturn are visible at the same time!

The best time will be after midnight on June 17. To see the best details, you’ll need a telescope.

Saturn will be at opposition on June 14, when Saturn, the Earth and the sun are in a straight line.

Opposition provides the best views of Saturn and several of its brightest moons. At the very least, you should be able to see Saturn’s moon Titan, which is larger and brighter than Earth’s moon.

As mentioned earlier, you’ll be able to see Jupiter and Saturn in the night sky this month. Through a telescope, you’ll be able to see the cloud bands on both planets. Saturn’s cloud bands are fainter than those on Jupiter.

You’ll also have a great view of Saturn’s Cassini Division, discovered by astronomer Giovanni Cassini in 1675, namesake of our Cassini spacecraft.

Our Cassini spacecraft has been orbiting the planet since 2004 and is on a trajectory that will ultimately plunge it into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, 2017, bringing the mission to a close.

Our Juno spacecraft recently completed its sixth Jupiter flyby. Using only binoculars you can observe Jupiter’s 4 Galilean moons - Io, Callisto, Ganymede and Europa.

To learn about What’s Up in the skies for June 2017, watch the full video:

For more astronomy events, check out NASA’s Night Sky Network at https://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

More Posts from Carlosalberthreis and Others

Hoje vamos falar um pouco de Urano.

Urano, as vezes é considerado como o paneta esquecido do nosso Sistema Solar, ele está muito longe, foi visitado só uma vez por uma sonda em 1986, pela Voyager II.

Urano é o sétimo planeta em distância do Sol, e o terceiro maior em tamanho, perdendo somente para Júptier e Saturno.

Urano possuem finos anéis de poeira e um conjunto incrível de 27 luas que nós conhecemos até hoje.

Na verdade é um pouco ridículo não termos tanto interesse assim, nesse grande planeta do nosso Sistema Solar.

Para vocês terem uma ideia, sabemos mais de Plutão e temos imagens mais detalhadas de Plutão do que de Urano.

Talvez o aspecto mais estranho de Urano seja a sua inclinação. Ele praticamente gira deitado.

Na verdade todos os planetas do Sistema Solar têm uma inclinação, a da Terra é de 23.5 graus, de Marte, 25 graus, e até Mercúrio tem uma inclinação de 2.1 graus.

Agora Urano, tem uma inclinação do eixo de rotação de 97.8 graus.

A grande questão então é, o que teria acontecido com Urano, para ter uma inclinação tão grande assim?

Para entender isso, teremos que voltar no início da história do Sistema Solar. A nossa vizinhança era um lugar bem violento e não muito amigável de se viver.

Muitas colisões aconteciam, entre corpos gigantescos, colisões catastróficas, vide a colisão da Terra com um corpo quase do tamanho de Marte que gerou a nossa Lua.

As colisões eram tão violentas, que os planetas mudavam de órbita, outros eram expulsos do Sistema Solar e outros mergulhavam diretamente na direção do Sol.

Com Urano, certamente aconteceu isso, uma colisão violenta que fez com que ele se inclinasse, e essa colisão aconteceu quando ele ainda estava circundado pelo disco de poeira que deu origem às suas luas, e nós sabemos disso, pois as luas orbitam Urano na mesma inclinação do seu eixo de rotação.

Os astrônomos atualmente acreditam que não foi uma única colisão que fez isso com Urano, mas sim uma série de colisões. Se fosse uma só, Urano giraria diferente, com uma série de colisões, elas agem como freios, colocando o planta na rotação correta.

Qual a consequência disso? Bem, imagine você na superfície de Urano (tudo bem, ele não tem superfície é uma bola de gás, mas imagine que tem), se você estivesse no polo você veria o Sol acima do horizonte por 42 anos, fazendo círculos cada vez maiores até desaparecer no horizonte, e depois ficaria 42 anos sem ver o Sol.

O Sistema Solar é feito de sobreviventes, e a nossa Terra, um sobrevivente mais sortudo ainda. Mas olhando para os outros planetas podemos ver que a vida realmente não foi fácil no início da história do Sistema Solar.

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nk_hBs2Ci48)

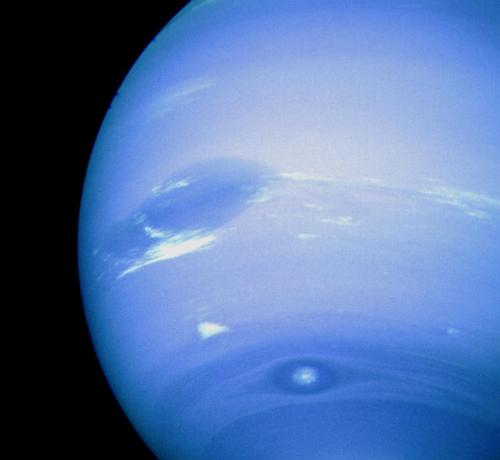

This photograph of Neptune was reconstructed from two images taken by Voyager 2’s narrow-angle camera, through the green and clear filters. At the north (top) is the Great Dark Spot, accompanied by bright, white clouds that undergo rapid changes in appearance.

Credit: NASA

26 de Abril de 2016 começa com Lua, planeta Saturno, planeta Marte, estrela Antares e chuva de meteoros Alfa-Escorpídeas. Um começo celeste bastante comemorativo! (em Parintins)

Nesta fotografia a nossa casa galáctica, a Via Láctea, estende-se ao longo do céu por cima da paisagem dos Andes chilenos. Em primeiro plano, as estradas para o Observatório de La Silla do ESO encontram-se cravejadas de telescópios astronômicos de vanguarda que apontam na direção da Via Láctea. Vários telescópios multinacionais foram capturados nesta imagem. O telescópio de 3,6 metros do ESO aparece no pedestal central e é neste telescópio que está montado o instrumento High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) — o melhor “caçador” de exoplanetas no mundo. Junto à cúpula principal, encontra-se o Coudé Auxiliary Telescope (CAT), que era utilizado para alimentar um potente espectrógrafo Coudé Echelle; neste momento estão ambos desativados. No sopé do pequeno monte está o Rapid Action Telescope for Trasient Objects (TAROT) francês, que segue eventos altamente energéticos chamados explosões de raios gama. Estes fenômenos são também estudados pelotelescópio suíço de 1,2 metros Leonhard Euler instalado na cúpula à esquerda, embora o seu enfoque seja a busca de exoplanetas. Ao fundo à direita podemos ver ainda o Swedish-ESO Submillimetre Telescope (SEST) que foi desativado em 2003 e substituído pelo Atacama Pathfinder EXperiment (APEX), situado no planalto do Chajnantor. Um mapa com todas as instalações existentes em La Silla pode ser consultado neste link. A grande densidade de instrumentos nas estradas de La Silla mostram o quão desejável é este sítio para as observações astronômicas. O local encontra-se longe de cidades muito iluminadas — o efeito dramático de tênues luzes de freio de um único carro pode ser visto à esquerda — e a altitude elevada.

Fonte:

http://www.eso.org/public/brazil/images/potw1610a/

çõe@i�(l�

Conjunction: Mars, Venus and Moon

by Stefan Grießinger

Juno Spacecraft: What Do We Hope to Learn?

The Juno spacecraft has been traveling toward its destination since its launch in 2011, and is set to insert Jupiter’s orbit on July 4. Jupiter is by far the largest planet in the solar system. Humans have been studying it for hundreds of years, yet still many basic questions about the gas world remain.

The primary goal of the Juno spacecraft is to reveal the story of the formation and evolution of the planet Jupiter. Understanding the origin and evolution of Jupiter can provide the knowledge needed to help us understand the origin of our solar system and planetary systems around other stars.

Have We Visited Jupiter Before? Yes! In 1995, our Galileo mission (artist illustration above) made the voyage to Jupiter. One of its jobs was to drop a probe into Jupiter’s atmosphere. The data showed us that the composition was different than scientists thought, indicating that our theories of planetary formation were wrong.

What’s Different About This Visit? The Juno spacecraft will, for the first time, see below Jupiter’s dense clover of clouds. [Bonus Fact: This is why the mission was named after the Roman goddess, who was Jupiter’s wife, and who could also see through the clouds.]

Unlocking Jupiter’s Secrets

Specifically, Juno will…

Determine how much water is in Jupiter’s atmosphere, which helps determine which planet formation theory is correct (or if new theories are needed)

Look deep into Jupiter’s atmosphere to measure composition, temperature, cloud motions and other properties

Map Jupiter’s magnetic and gravity fields, revealing the planet’s deep structure

Explore and study Jupiter’s magnetosphere near the planet’s poles, especially the auroras – Jupiter’s northern and southern lights – providing new insights about how the planet’s enormous

Juno will let us take a giant step forward in our understanding of how giant planets form and the role these titans played in putting together the rest of the solar system.

For updates on the Juno mission, follow the spacecraft on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Tumblr.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

What is Gravitational Lensing?

A gravitational lens is a distribution of matter (such as a cluster of galaxies) between a distant light source and an observer, that is capable of bending the light from the source as the light travels towards the observer. This effect is known as gravitational lensing, and the amount of bending is one of the predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

This illustration shows how gravitational lensing works. The gravity of a large galaxy cluster is so strong, it bends, brightens and distorts the light of distant galaxies behind it. The scale has been greatly exaggerated; in reality, the distant galaxy is much further away and much smaller. Credit: NASA, ESA, L. Calcada

There are three classes of gravitational lensing:

1° Strong lensing: where there are easily visible distortions such as the formation of Einstein rings, arcs, and multiple images.

Einstein ring. credit: NASA/ESA&Hubble

2° Weak lensing: where the distortions of background sources are much smaller and can only be detected by analyzing large numbers of sources in a statistical way to find coherent distortions of only a few percent. The lensing shows up statistically as a preferred stretching of the background objects perpendicular to the direction to the centre of the lens. By measuring the shapes and orientations of large numbers of distant galaxies, their orientations can be averaged to measure the shear of the lensing field in any region. This, in turn, can be used to reconstruct the mass distribution in the area: in particular, the background distribution of dark matter can be reconstructed. Since galaxies are intrinsically elliptical and the weak gravitational lensing signal is small, a very large number of galaxies must be used in these surveys.

The effects of foreground galaxy cluster mass on background galaxy shapes. The upper left panel shows (projected onto the plane of the sky) the shapes of cluster members (in yellow) and background galaxies (in white), ignoring the effects of weak lensing. The lower right panel shows this same scenario, but includes the effects of lensing. The middle panel shows a 3-d representation of the positions of cluster and source galaxies, relative to the observer. Note that the background galaxies appear stretched tangentially around the cluster.

3° Microlensing: where no distortion in shape can be seen but the amount of light received from a background object changes in time. The lensing object may be stars in the Milky Way in one typical case, with the background source being stars in a remote galaxy, or, in another case, an even more distant quasar. The effect is small, such that (in the case of strong lensing) even a galaxy with a mass more than 100 billion times that of the Sun will produce multiple images separated by only a few arcseconds. Galaxy clusters can produce separations of several arcminutes. In both cases the galaxies and sources are quite distant, many hundreds of megaparsecs away from our Galaxy.

Gravitational lenses act equally on all kinds of electromagnetic radiation, not just visible light. Weak lensing effects are being studied for the cosmic microwave background as well as galaxy surveys. Strong lenses have been observed in radio and x-ray regimes as well. If a strong lens produces multiple images, there will be a relative time delay between two paths: that is, in one image the lensed object will be observed before the other image.

As an exoplanet passes in front of a more distant star, its gravity causes the trajectory of the starlight to bend, and in some cases results in a brief brightening of the background star as seen by a telescope. The artistic concept illustrates this effect. This phenomenon of gravitational microlensing enables scientists to search for exoplanets that are too distant and dark to detect any other way.Credits: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

Explanation in terms of space–time curvature

Simulated gravitational lensing by black hole by: Earther

In general relativity, light follows the curvature of spacetime, hence when light passes around a massive object, it is bent. This means that the light from an object on the other side will be bent towards an observer’s eye, just like an ordinary lens. In General Relativity the speed of light depends on the gravitational potential (aka the metric) and this bending can be viewed as a consequence of the light traveling along a gradient in light speed. Light rays are the boundary between the future, the spacelike, and the past regions. The gravitational attraction can be viewed as the motion of undisturbed objects in a background curved geometry or alternatively as the response of objects to a force in a flat geometry.

A galaxy perfectly aligned with a supernova (supernova PS1-10afx) acts as a cosmic magnifying glass, making it appear 100 billion times more dazzling than our Sun. Image credit: Anupreeta More/Kavli IPMU.

To learn more, click here.

Celestial Geometry: Equinoxes and Eclipses

March 20 marks the spring equinox. It’s the first day of astronomical spring in the Northern Hemisphere, and one of two days a year when day and night are just about equal lengths across the globe.

Because Earth is tilted on its axis, there are only two days a year when the sun shines down exactly over the equator, and the day/night line – called the terminator – runs straight from north to south.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the March equinox marks the beginning of spring – meaning that our half of Earth is slowly tilting towards the sun, giving us longer days and more sunlight, and moving us out of winter and into spring and summer.

An equinox is the product of celestial geometry, and there’s another big celestial event coming up later this year: a total solar eclipse.

A solar eclipse happens when the moon blocks our view of the sun. This can only happen at a new moon, the period about once each month when the moon’s orbit positions it between the sun and Earth — but solar eclipses don’t happen every month.

The moon’s orbit around Earth is inclined, so, from Earth’s view, on most months we see the moon passing above or below the sun. A solar eclipse happens only on those new moons where the alignment of all three bodies are in a perfectly straight line.

On Aug. 21, 2017, a total solar eclipse will be visible in the US along a narrow, 70-mile-wide path that runs from Oregon to South Carolina. Throughout the rest of North America – and even in parts of South America, Africa, Europe and Asia – the moon will partially obscure the sun.

Within the path of totality, the moon will completely cover the sun’s overwhelmingly bright face, revealing the relatively faint outer atmosphere, called the corona, for seconds or minutes, depending on location.

It’s essential to observe eye safety during an eclipse. Though it’s safe to look at the eclipse ONLY during the brief seconds of totality, you must use a proper solar filter or indirect viewing method when any part of the sun’s surface is exposed – whether during the partial phases of an eclipse, or just on a regular day.

Learn more about the August eclipse at eclipse2017.nasa.gov.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

-

marreiros-blog1 liked this · 1 year ago

marreiros-blog1 liked this · 1 year ago -

dgtrekker reblogged this · 1 year ago

dgtrekker reblogged this · 1 year ago -

askvekullerr liked this · 3 years ago

askvekullerr liked this · 3 years ago -

crabgirl69-blog liked this · 6 years ago

crabgirl69-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

diddisgirl4life reblogged this · 6 years ago

diddisgirl4life reblogged this · 6 years ago -

cem-serhildan liked this · 6 years ago

cem-serhildan liked this · 6 years ago -

cryptomosquito liked this · 6 years ago

cryptomosquito liked this · 6 years ago -

israelquinones9 liked this · 6 years ago

israelquinones9 liked this · 6 years ago