Ok . Snapedom, I Have A Question. Wake Up

ok . Snapedom, I have a question. Wake up

In the chapter 33 of DH We have The Prince’s Tale where there are some memories that Snape passes on to Harry in order to help him: 1) to inform him what to do & 2) convince him that it is not fake news. Snape’s genuine about being at the order side n “yeah…Harry, you truly have to die”. BUT I notice the some memories were passed sorely at Snape’s will. Like that one where it’s said: “delighted to find himself famous, attention-seeking n impertinent”. Like for me with this memory he’s saying….“I was wrong about you”. But there’s ONE memory that I don’t know what the fuck it is about. That one that takes place at Grimauld’s Place. Im clueless 1) why was he there? 2) was it him that created that mess or Mundungus Fletcher? 3) If 2 was him why didn’t he put the things in order before leave? 4) that memory was so intimist. Where’s the purpose to show this to Harry? 5) why take that specific piece of letter? it was for himself or to keep Dumbledore’s secret? why take that piece of photography? 6) and much more. As I said I’m clueless over what that moment was all about.

More Posts from Dreamsp023 and Others

'the temptation of saint anthony (first series),' ten lithographs by odilon redon; french c. 1888.

John Nettleship and the roots of Severus Snape

I wrote some of this earlier as a reblog to one of @feelabitfree posts, but I feel like more people could be interested in the subject, so I’m putting it in its own post for the general tag.

So this is about John Nettleship, the man who was one of JK Rowling’s inspirations to create the character of Severus Snape.

He was Head of Science at Wyedean School in Sedbury, Gloucestershire, where he taught Chemistry to JK, who began studying at the school in September 1976. Her mother, Anne, worked as a technician in the Science department from 1978. He was often known as “Stinger” by pupils due to his last name being “Nettleship”.

Yes, those are images of Mr. Nettleship in his science lab.

I learned that John, even though he was surprised and mortified at first, later on felt honored for his connection to Severus and wanted it to be remembered. This is all taken from this article, which provides detailed information about… a bit of everything (really), from people who knew him well. There is also this condensed version of it. (And I’d say: do visit the source, there’s a lot of interesting info on other stuff about Snape in there).

John at the time that he taught Rowling was in his thirties, like Snape in the books; whip-thin and (in the words of a former student) “ghostly white”, with swinging curtains of long and often rather greasy black hair, a burning gaze, an intense manner, irregular teeth and a rather large nose, and was often a bit scruffy and unkempt, even though he was always fastidiously clean.

This is John in 1976, 4 weeks after JK started at Wyedean.

He was a lifelong Labour Party activist and he later became a much-re-elected local councillor.

An innovative, inspirational teacher and an advocate of child-centred learning, John cared deeply about teaching and about his students, but when Rowling knew him his first marriage was failing and he was dazed with insomnia, which explains why Snape is so angry and excitable. He also had to compensate for looking about eighteen - and for the children’s mockery of his social clumsiness.

(…) As a child he suffered extreme physical abuse from youths running a Cub Scouts troop. At the school he taught at before Wyedean his colleagues marginalised and bullied him for his outspoken independence, and at both schools he endured Marauder-like verbal and physical attacks from certain students: but at both there were also students who admired and supported him.

(…) He remembered Rowling, who had spent her break-times in the office he shared with her mother, with fond admiration, and became an active fan who conducted Snape-tours while wearing an academic gown, and lectured on likely local inspirations for people and places in the Potterverse.

Photos of John when he was 39 and 41 years old, respectively (second one was cut by himself because he didn’t want the entire world seeing his nipples, but the writer of the article makes a point to stress that he had remarkably thin arms).

John did the Rowling family a great favour, for as Head of Science at Wyedean Comprehensive in Sedbury he hired Anne Rowling, a woman already partially disabled by multiple sclerosis and almost certain to get worse, at a time when no-one else would, and took her on as a Biology lab. assistant. He remembered Anne as a jolly, humorous woman with what she herself called “a dirty great laugh”. He was enormously fond of her and fought the school tooth and nail to get improved disability-access for her: in particular, to have a lavatory installed in the science block so she wouldn’t have to struggle back to the main building several times a day. All that is unambiguously good in Snape, his intelligence, wit and passion for his subject, his showmanship and fluency, his protectiveness of others, his courage, love, loyalty, honesty, dedication and sense of duty, his independence and his moral seriousness, is identifiably derived from John.

There is some discussion in the article about how he believed he probably had Asperger’s Syndrome and so some of his behaviour was actually due to missing social cues and not out of spite and rage as JK maybe interpreted (and wrote Snape’s background in order to explain).

In JK’s drawings of him, Snape often has a stubble and is shown wearing a Dracula-collared cloak which are never described as such in the books, but could be inspired by John and this high-collared hippyish jacket he used to wear.

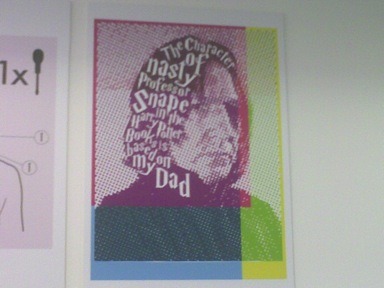

Also, let me show the Snape fandom this thing his son made because it is adorable and you’ll feel proud:

Now I want to finish this long ass post with this: John also enjoyed singing! And if you’re interested in hearing the original strong baritone voice that inspired our favorite overgrown bat, you can do that right here (there’s also a video on the link).

Professor Remus Lupin on platform 9 ¾ before he boards the train to Hogwarts.

Lupin is one of my absolute favorite HP characters, so it was about time I drew him!<3

Here is a model/contraption i created based around Haydens ring theory. This diagram has been heavily inspired by various old planetarium and astronomy diagrams i dug up. I wanted to create my own imaginary diagram of what this would look like, of course having the diagram designed for an earlier time. You may also notice hints of Etienne’s designs throughout, such as pinholes in the cenotaph from him memorial to Isaac newton :) Im not used go creating anything in such detail so i am quite pleased with the outcome, Enjoy :)

@mothercain <3

@mothercain

Photos ~ silkenweinberg

There is a thing that deeply disturbes me about Severus' behaviour in SWM. He just wrote a very important exam on a subject that we know he loves and deeply cares about. He probably had been diligently preparing for it for a very long time, was anxious and aspiring how all the studious kids usually are. A normal teen behaviour is sharing how you wrote it with your friends – this is exactly what the Marauders do. But Severus approaches no one, talks to no one. Lily is hanging out with her other friends – he isn't invited to spend time with them, nor is he exchanging at least a couple of words with Lily personally. While she clearly has other people to chat with, Severus doesn't talk to any slytherins, not Mulcibier or Avery or anyone else. And he doesn't seek anyone out too, he just settles with reading alone like it's normal. Yes, he is introverted, but even the most introverted person would like to share such an important event with someone close to them.

It's like Severus had absolutely no one in that school who cared enough to hear about his pride and joy of writing the exam well, or his worries on getting something wrong. It's like he didn't even expect anyone to care. It is clear from everything in that scene that he is painfully lonely and largely ostracised, that him and Lily aren't particularly close at that point, and that he doesn't have any "gang" or any good friends in slytherin either.

a few great films that are free on the internet archive

in decent quality too!

here is the archive collection of these films so you can favorite on there/save if desired.

links below

black girl (1966) dir. ousmane sembene

the battle of algiers (1966) dir. gillo pontecorvo

paris, texas (1984) dir. wim wenders

desert hearts (1985) dir. donna deitch

harold and maude (1973) dir. hal ashby

los olvidados (1952) dir. luis bunuel

walkabout (1971) dir. nicolas roag

rope (1948) dir alfred hitchcock

freaks (1932) dir. tod browning

frankenstein (1931) dir. james whale

sunset boulevard (1950) dir billy wilder

fantastic planet (1973) dir. rené laloux

jeanne dielman (1975) dir. chantal akerman

the color of pomegranates (1969) dir. sergei parajanov

all about eve (1950) dir. joseph l. mankiewicz

gilda (1946) dir. charles vidor

the night of the hunter (1950) dir. charles laughton

the invisible man (1931) dir. james whale

COLLECTION of georges méliès shorts

rebecca (1940) dir. alfred hitchcock

brief encounter (1946) dir. david lean

to be or not to be (1942) dir. ernst lubitsch

a place in the sun (1951) dir george stevens

eyes without a face (1960) dir. georges franju

double indeminity (1944) dir. billy wilder

wild strawberries (1957) dir. ingmar bergman

shame (1968) dir. ingmar bergman

through a glass darkly (1961) dir. ingmar bergman

persona (1961) dir. ingmar bergman

winter light (1963) dir. ingmar bergman

the ascent (1977) dir. larisa shepitko

the devil, probably (1977) dir. robert bresson

cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) dir. agnes varda

alien (1979) dir. ridley scott + its sequels

after hours (1985) dir. martin scorsese

halloween (1978) dir. john carpenter

the watermelon woman (1996) dir. cheryl dune

EDIT: part two here + the letterboxd list

My problem with Lily and James being seen as a super couple has nothing to do with Severus Snape but rather with the fact that when we look at the relationship between James and Lily through a feminist lens, it’s hard not to notice some pretty glaring issues that go beyond just whether or not they’re an “OTP” couple. Sure, on the surface it might seem like a story of two people finding love amid all the chaos, but scratch beneath the surface and you see a whole lot more about toxic masculinity, objectification, and the erasure of a woman’s agency. James is celebrated as this charming, rebellious “bad boy” with a roguish smile, while Lily gets stuck playing the role of the sacrificial, moral compass woman—someone who exists largely to balance out and even redeem the male narrative. And honestly, that’s a problem.

James is shown as this complex, active character who’s constantly surrounded by friends, enemies, and drama. His life is dynamic and full of choices—even if those choices sometimes involve manipulation and deceit. He’s the kind of guy who can easily slip out of confinement with his Invisibility Cloak, leaving Lily behind in a narrative that, over time, turns her into a background figure. This dynamic isn’t accidental; it’s reflective of how our culture often values male agency over female independence. Lily, on the other hand, is repeatedly reduced to her relationships with the men around her. Instead of being a person with her own dreams, opinions, and friendships, she becomes a symbol—a kind of emotional barometer for how “good” or “bad” a man is. Her character is used to validate the actions of others, which means her individuality gets smothered under the weight of a trope that’s all too common in literature: the idea that a woman’s worth is measured by her ability to tame or save a troubled man.

This isn’t just about a lack of depth in Lily’s character; it’s also about how her portrayal reinforces harmful gender norms. Lily is depicted as this kind of sacrificial mother figure—a person whose primary virtue is her selflessness, her willingness to suffer and sacrifice for the sake of others. While selflessness is often celebrated in women, it’s a double-edged sword when that selflessness is the only thing we see. Instead of having her own narrative, her role is defined by how much she gives up, not by what she contributes or the inner life she leads. And it’s not just a narrative oversight—it’s a reflection of a broader cultural pattern where women are expected to be nurturing, supportive, and ultimately secondary to the male characters who drive the action.

What’s even more frustrating is how Lily’s isolation is used to further the narrative of James’s redemption. Over time, we see Lily’s network of friends and her connections outside of James gradually disappear. It’s almost as if, once she falls in love, her entire world is meant to shrink around that relationship. And here’s where the feminist critique really kicks in: this isn’t a realistic depiction of a balanced, healthy relationship—it’s a story that subtly suggests that a woman’s fulfillment comes from being dependent on one man and his circle, rather than cultivating her own identity. Meanwhile, James continues to be portrayed as this larger-than-life figure who’s got a whole world beyond his romantic entanglement, a world filled with vibrant interactions, rivalries, and a legacy that extends beyond his relationship with Lily.

Another point worth mentioning is the way in which the narrative seems to excuse James’s less-than-stellar behavior. His manipulation, his lying, and his willingness to trick Lily into situations that serve his own interests are brushed off as quirks of a “bad boy” persona—a kind of charm that, in the end, makes him redeemable because Lily’s love is supposed to “tame” him. This kind of storytelling not only normalizes toxic masculinity but also puts an unfair burden on Lily. It’s like saying, “Look how amazing you are, you’re the only one who can fix him!” That’s a dangerous message because it implies that women are responsible for managing or even reforming male behavior, rather than holding men accountable for their own actions.

The imbalance in their character development is glaringly obvious when you compare how much more we learn about James versus how little we know about Lily. James is given room to be flawed, to grow, and to be complicated. His friendships, his rivalries, and even his mistakes are all part of what makes him a rounded character. Lily, however, is often just a name, a face in the background who exists mainly to serve as a counterpoint to James’s narrative. Her inner life, her ambitions, and her struggles are rarely explored in any meaningful way, leaving her as a one-dimensional character whose only real purpose is to highlight the moral journey of the man she loves.

It’s also important to recognize how this kind of narrative plays into broader cultural ideas about gender. When literature consistently portrays women as the quiet, isolated figures who are only valuable in relation to the men around them, it sends a message about what is expected of real-life women. It suggests that a woman’s worth is determined by how much she sacrifices or how well she can support a man, rather than by her own achievements or personality. This isn’t just a harmless trope—it contributes to a societal mindset that limits women’s potential and reinforces gender inequality. The way Lily is written reflects a kind of “tamed” femininity that’s supposed to be passive, supportive, and ultimately secondary to the active, adventurous masculinity that James represents.

At the heart of the issue is the lack of balance in their relationship as depicted in the texts. The idea that Lily “fell for” a man who was clearly not a paragon of virtue is problematic, but what’s even more problematic is how her role in the relationship is so narrowly defined. Rather than being seen as an independent character who makes choices and has her own voice, she is constantly portrayed as someone whose existence is meant to validate the male experience. Even when the texts mention that Lily had her own issues—like hating James at times or suffering because of the way their relationship unfolded—it’s always in a way that underlines her weakness compared to James’s dynamic, active presence.

Looking at the broader picture, it’s clear that this isn’t just about one fictional couple—it’s a reflection of how gender dynamics have long been skewed in literature. Male characters are given the freedom to be complex, flawed, and full of life, while female characters are often stuck in roles that don’t allow them to be fully realized. This isn’t to say that every story with a sacrificial female character is inherently bad, but it does mean that when a character like Lily is reduced to a mere symbol—a moral compass or a measure of male worth—it’s time to ask why and what that says about the society that produced that narrative.

So, what’s the way forward? For one, we need to start reimagining these relationships in a way that allows both partners to be fully fleshed out. Lily deserves to be more than just a side character or a moral benchmark; she should have her own narrative, her own dreams, and her own agency. And as much as it might be appealing to think of James as this redeemable rebel, it’s equally important to hold him accountable for the ways in which his behavior perpetuates harmful stereotypes about masculinity. A healthier narrative would be one in which both characters grow together, where mutual respect and equal agency are at the core of their relationship.

In the end, the story of James and Lily, as it stands, is a reminder of how deeply ingrained gender norms can shape the stories we tell. It’s a cautionary tale about the dangers of allowing toxic masculinity to go unchecked and of confining women to roles that don’t do justice to their full humanity. For anyone who’s ever felt frustrated by these imbalances, there’s hope in the idea of re-writing these narratives—of pushing for stories where both men and women are seen as complete, complex individuals. And really, that’s what literature should strive for: a reflection of the messy, beautiful, and often complicated reality of human relationships, where no one is just there to serve as a prop in someone else’s story.

Ultimately, if we can start imagining a world where characters like Lily aren’t just defined by their relationships to men, where their voices and stories are given as much weight as those of their male counterparts, then we can begin to chip away at the outdated tropes that have held us back for so long. It’s about time we celebrated the full spectrum of human experience—and that means giving women like Lily the space to shine on their own terms, without being constantly overshadowed by a “bad boy” narrative that has little to say about their true selves.

I can’t stand another day of my life without saying that Rick Owens, fashion designer, is the most accurate representation of what Snape from the books would look like.

Guys, it's really creapy . This isn't a "looks alike" thing. When I come across photos of this man my first reaction is to think that it’s a super realistic Snape fanart. Lol the way Owens looks like Snape is insane. He's his identical twin brother!!

Why I've never seen anyone saying that?

-

princediffido reblogged this · 2 months ago

princediffido reblogged this · 2 months ago -

dreamsp023 reblogged this · 2 months ago

dreamsp023 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cyan-cyun liked this · 2 months ago

cyan-cyun liked this · 2 months ago -

dreamsp023 liked this · 2 months ago

dreamsp023 liked this · 2 months ago -

beatifysaints liked this · 2 months ago

beatifysaints liked this · 2 months ago -

sideprince reblogged this · 2 months ago

sideprince reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cherryberrytree liked this · 2 months ago

cherryberrytree liked this · 2 months ago -

remus-poopin reblogged this · 2 months ago

remus-poopin reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lovelyiknow liked this · 5 months ago

lovelyiknow liked this · 5 months ago -

fireandapples liked this · 7 months ago

fireandapples liked this · 7 months ago -

kaletatzee liked this · 8 months ago

kaletatzee liked this · 8 months ago -

quicksilverlightning liked this · 9 months ago

quicksilverlightning liked this · 9 months ago -

starlight95tonight liked this · 9 months ago

starlight95tonight liked this · 9 months ago -

a-grey-lining liked this · 10 months ago

a-grey-lining liked this · 10 months ago -

qijtai liked this · 10 months ago

qijtai liked this · 10 months ago -

mikailakay liked this · 10 months ago

mikailakay liked this · 10 months ago -

nerwenposts liked this · 10 months ago

nerwenposts liked this · 10 months ago -

cats-wolverine liked this · 11 months ago

cats-wolverine liked this · 11 months ago -

ramssby liked this · 11 months ago

ramssby liked this · 11 months ago -

hollyparker liked this · 11 months ago

hollyparker liked this · 11 months ago -

sillytenebra liked this · 11 months ago

sillytenebra liked this · 11 months ago -

tajiklove liked this · 11 months ago

tajiklove liked this · 11 months ago -

line-of-ants liked this · 11 months ago

line-of-ants liked this · 11 months ago -

wolfie-the-randomness liked this · 11 months ago

wolfie-the-randomness liked this · 11 months ago -

spamelotte liked this · 11 months ago

spamelotte liked this · 11 months ago -

susiehlll liked this · 11 months ago

susiehlll liked this · 11 months ago -

sireseverussnape reblogged this · 11 months ago

sireseverussnape reblogged this · 11 months ago -

sireseverussnape liked this · 11 months ago

sireseverussnape liked this · 11 months ago -

stuckinfictionalworlds liked this · 11 months ago

stuckinfictionalworlds liked this · 11 months ago -

hicanivent liked this · 11 months ago

hicanivent liked this · 11 months ago -

dexteritymisdirectionsuggestion liked this · 11 months ago

dexteritymisdirectionsuggestion liked this · 11 months ago -

thisisnotjuli liked this · 11 months ago

thisisnotjuli liked this · 11 months ago -

drarryshipperandsnover reblogged this · 11 months ago

drarryshipperandsnover reblogged this · 11 months ago -

drarryshipperandsnover liked this · 11 months ago

drarryshipperandsnover liked this · 11 months ago -

thevanishingdot reblogged this · 11 months ago

thevanishingdot reblogged this · 11 months ago -

snapecentric reblogged this · 11 months ago

snapecentric reblogged this · 11 months ago -

snapecentric liked this · 11 months ago

snapecentric liked this · 11 months ago -

citrusotakutea liked this · 11 months ago

citrusotakutea liked this · 11 months ago -

artepathosm reblogged this · 11 months ago

artepathosm reblogged this · 11 months ago -

artepathosm liked this · 11 months ago

artepathosm liked this · 11 months ago -

dias-therealone liked this · 11 months ago

dias-therealone liked this · 11 months ago -

najmzzz liked this · 11 months ago

najmzzz liked this · 11 months ago -

liaaaara liked this · 11 months ago

liaaaara liked this · 11 months ago -

dearestdo3 reblogged this · 11 months ago

dearestdo3 reblogged this · 11 months ago -

merryhaze reblogged this · 1 year ago

merryhaze reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dinarosie liked this · 1 year ago

dinarosie liked this · 1 year ago

9w8 sx INTP | 21 | Spanish Here I talk about tarot and sometimes I do movie reviews.

65 posts