After The Rain At Botanic Garden Of The Jagiellonian University 🕸️🌱

After the rain at Botanic Garden of the Jagiellonian University 🕸️🌱

My photography; Kraków, VI 2024

More Posts from Rpodnee-blog and Others

I think the moment that convinced me the operating logic of our society is truly fucked in a way that cannot merely be reformed was after that eclipse in 2017 when the articles started coming out about how much money had been lost by productivity dropping from people stopping momentarily to watch it happen. To measure the world by the metric of the dollar to such a devotion that any cult leader would be jealous of that you would look at one of the most sublime experiences in nature which we, our ancestors, and even a not insignificant number of non-human species, have been observing in awestruck wonder for millennia, and decide that such a moment of profundity is something to be fought and preferably expunged from the human experience because it briefly impacts quarterly revenue.

It's a feeling that has been coming up repeatedly, but with increasing frequency in the last few years. That being: what is all of this for? Where are we going? Nobody who defends the status quo can seem to answer it. What's the point of an uninterrupted quarterly revenue stream if we can't even look at an eclipse every few years? What's the point of hustling and grinding 50, 60, 70 hour weeks if you never have time to have dinner with your friends, talk to your family on the phone, but on a bigger spectrum, what's the point of all of that if you still don't have any way of retiring in the future? With the way that our lives are being increasingly monetized and squeezed every second, what is there to look forward to?

Saint Olga by Milhail Nesterov

Oil on canvas, (1892-1893)

New Zealand's Goblin Forest

Honoured to have received some wonderful results from this year’s @greatwalksmag Wilderness Photographer of the Year competition, including a win for ‘Creatures in the Shadows’ (photo 1)

benjamin.maze

In the first poetry workshop I ever took my professor said we could write about anything we wanted except for two things: our grandparents and our dogs. She said she had never read a good poem about a dog. I could only remember ever reading one poem about a dog before that point—a poem by Pablo Neruda, from which I only remembered the lines “We walked together on the shores of the sea/ In the lonely winter of Isla Negra.” Four years later I wrote a poem about how when I was a little girl I secretly baptized my dog in the bathtub because I was afraid she wouldn’t get into heaven. “Is this a good poem?” I wondered. The second poetry workshop, our professor made us put a bird in each one of our poems. I thought this was unbelievably stupid. This professor also hated when we wrote about hearts, she said no poet had ever written a good poem in which they mentioned a heart. I started collecting poems about hearts, first to spite her, but then because it became a habit I couldn’t break. The workshop after that, our professor would tell us the same story over and over about how his son had died during a blizzard. He would cry in front of us. He never told us we couldn’t write about anything, but I wrote a lot of poems about snow. At the end of the year he called me into his office and said, “looking at you, one wouldn’t think you’d be a very good writer” and I could feel all the pity inside of me curdling like milk. The fourth poetry workshop I ever took my professor made it clear that poets should not try to engage with popular culture. I noticed that the only poets he assigned were men. I wrote a poem about that scene in Grease 2 where a boy takes his girlfriend to a fallout shelter and tries to get her to have sex with him by tricking her into believing that nuclear war had begun. It was the first poem I ever published. The fifth poetry workshop I ever took our professor railed against the word blood. She thought that no poem should ever have the word “blood” in it, they were bloody enough already. She returned a draft of my poem with the word blood crossed out so hard the paper had torn. When I started teaching poetry workshops I promised myself I would never give my students any rules about what could or couldn’t be in their poems. They all wrote about basketball. I used to tally these poems when I’d go through the stack I had collected at the end of each class. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 poems about basketball. This was Indiana. Eventually I couldn’t take it anymore. I told the class, “for the next assignment no one can write about basketball, please for the love of god choose another topic. Challenge yourselves.” Next time I collected their poems there was one student who had turned in another poem about basketball. I don’t know if he had been absent on the day I told them to choose another topic or if he had just done it to spite me. It’s the only student poem I can still really remember. At the time I wrote down the last lines of that poem in a notebook. “He threw the basketball and it came towards me like the sun”

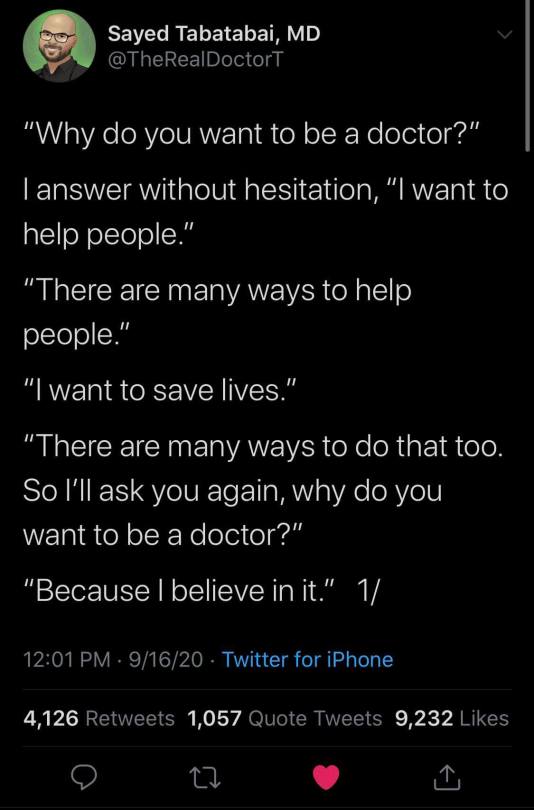

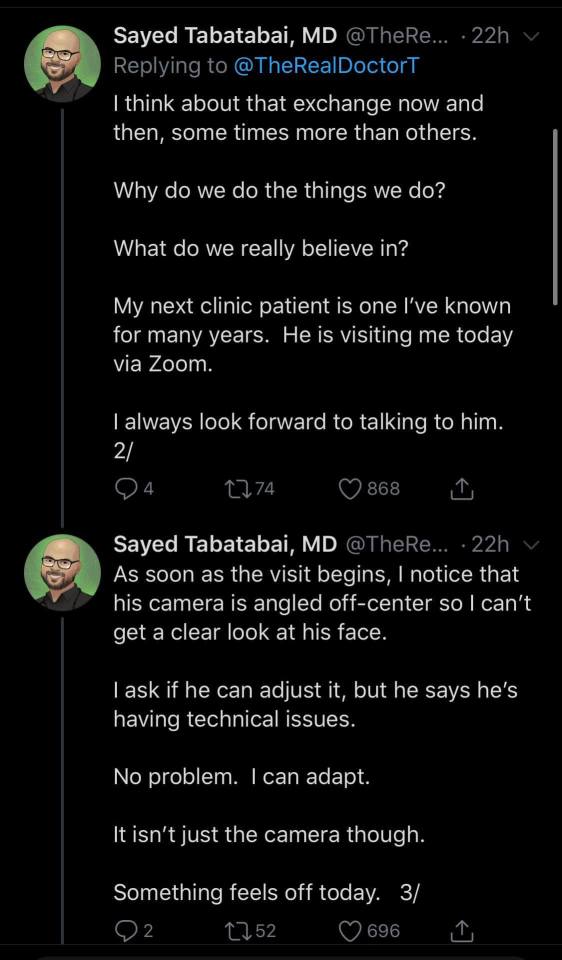

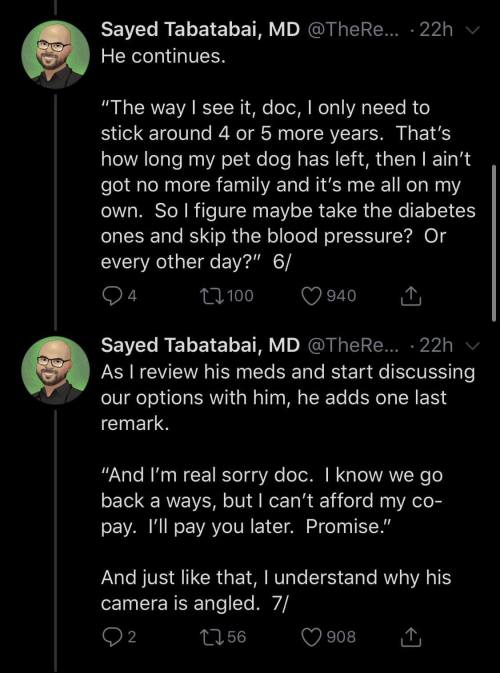

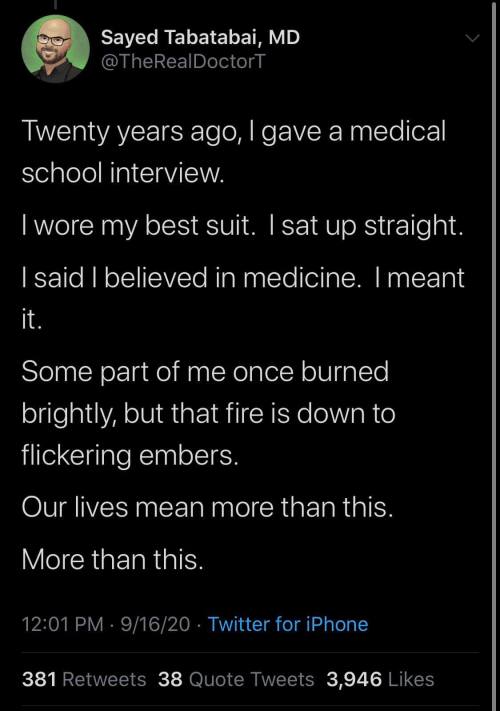

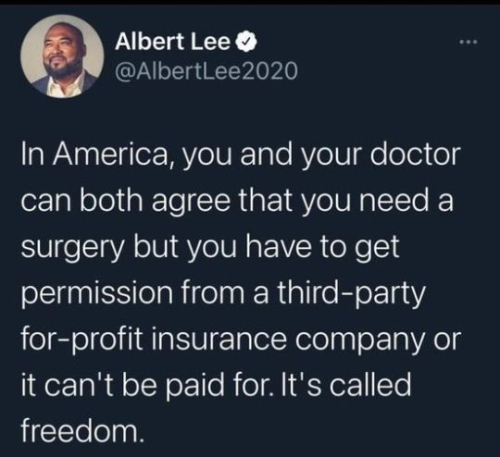

Our system is broken. It is cruel. It is dehumanizing, degrading, and it’s vile nature is so, so unnecessary.

We need universal healthcare today in America. We needed it 40 years ago. It’s cheaper, it’s simpler, it’s more efficient, it’s more effective and it is so, so, so much less cruel than what we have.

Additional sources/references:

Universal Healthcare Cost in America would be cheaper by trillions of dollars

The US has worse life expectancies than socialized healthcare countries

We have worse generalized healthcare results

We have the most expensive care

Our system is so cruel and unique that doctors from other countries literally can’t believe what happens here

I can’t tell you where or how to activate to help solve this. There are politicians, groups, and activists pushing for this in so many ways. I can tell you when, though.

Now.

how can you be so controversial and yet so brave

(reposted from Twitter)

Hey so, have I ever told you about the time I was at an interfaith event (my rabbi, who was on the panel, didn't want to be the only Jew there), and there was a panel with representatives of 7 different traditions, from Baha'i to Zoroastrian?

The setup was each panelist got asked the same question by the moderator, had 3 minutes to respond, and then they moved on to the next panelist.

The Christian dude talked for 8 minutes and kept waving off the poor, flustered, terminally polite Unitarian moderator.

The next panelist was a Hindu lady, who just said drily, "I'll try to keep my answer to under a minute so everyone else still has a chance to answer." (I, incidentally, am at a table with I think the only other non-Christian audience members, a handful of Muslims and a Zorastrian.)

So then we get to the audience questions part. No one's asking any questions, so finally I decide to get things rolling, and raise my hand and the very polite moderator comes over and gives me the mic.

I briefly explain Stendahl's concept of "holy envy" and ask what each of theirs is.

(If you're not familiar, Stendahl had 3 tenets for learning about other traditions, and one was leave room for "holy envy," being able to say, I am happy in my tradition and don't desire to convert, but this is something about another tradition that I admire and wish we had.)

The answers were lovely. My rabbi said she admired the Buddhist comfort with silence and wished we could learn to have that spaciousness in our practice. The Hindu said she admired the Jewish and Muslim commitment to social justice & changing, rather than accepting, the status quo.

The Christian dude said he envied that everyone else on the panel had the opportunity to newly accept Jesus.

I shit you not.

Dead silence. The Buddhist and Baha'i panelists are resolutely holding poker faces. The Hindu lady has placed her hands on the table and folded them and seems to be holding them very tightly. Over on the middle eastern end of the table, the rabbi, the imam, and the Zoroastrian lady are all leaning away from the Christian at identical angles with identical expressions of disgust. The terminally polite Unitarian moderator is literally wringing his hands in distress.

A Christian lady at the table next to me, somehow unable to pick up on the emotional currents in the room, sighs happily and says to her fellow church lady, "What a beautiful answer."

anyway I love my rabbi to death and would do anything for her

except attend another interfaith event

Me, after forgetting to cut the top off an onion before dicing it: “Aw dammit”

The Gordon Ramsey that lives in my head: “Don’t worry there, this mistake isn’t going to ruin anything. No need to be too hard on yourself”

Me: “Wow, that’s…not what I was expecting”

Gordon: “Of course, you ought to know by now that I don’t shout at cooks just to do so. I do it because the people in hit television show Kitchen Nightmares are putting their services out into the public and claim to be good enough to have the title of head chef. You’re just some guy in your twenties making beef stroganoff for yourself and your roommate. I’m kind of a dick, yeah, but I’m not gonna scream at you for a minor mistake like this”

Me: “Oh….well…thanks”

Gordon: “You’re welcome…cunt…”

Art by Ma-ko

the thing about being alone is that it’s so peaceful and freeing and cool apart from the evenings you descend into literal hell

one of the more valuable things I’ve learned in life as a survivor of a mentally unstable parent is that it is likely that no one has thought through it as much as you have.

no, your friend probably has not noticed they cut you off four times in this conversation.

no, your brother didn’t realize his music was that loud while you were studying.

no, your bff or S.O. doesn’t remember that you’re on a tight deadline right now.

no, no one else is paying attention to the four power dynamics at play in your friend group right now.

a habit of abused kids, especially kids with unstable parents, is the tendency to notice every little detail. We magnify small nuances into major things, largely because small nuances quickly became breaking points for parents. Managing moods, reading the room, perceiving danger in the order of words, the shift of body weight….it’s all a natural outgrowth of trying to manage unstable parents from a young age.

Here’s the thing: most people don’t do that. I’m not saying everyone else is oblivious, I’m saying the over analysis of minor nuances is a habit of abuse.

I have a rule: I do not respond to subtext. This includes guilt tripping, silent treatments, passive aggressive behavior, etc. I see it. I notice it. I even sometimes have to analyze it and take a deep breath and CHOOSE not to respond. Because whether it’s really there or just me over-reading things that actually don’t mean anything, the habit of lending credence to the part of me that sees danger in the wrong shift of body weight…that’s toxic for me. And dangerous to my relationships.

The best thing I ever did for myself and my relationships was insist upon frank communication and a categorical denial of subtext. For some people this is a moral stance. For survivors of mentally unstable parents this is a requirement of recovery.

-

6-iz reblogged this · 4 days ago

6-iz reblogged this · 4 days ago -

6-iz liked this · 4 days ago

6-iz liked this · 4 days ago -

sabiaspalabrasdepablo reblogged this · 4 days ago

sabiaspalabrasdepablo reblogged this · 4 days ago -

sabiaspalabrasdepablo liked this · 4 days ago

sabiaspalabrasdepablo liked this · 4 days ago -

malusrecord liked this · 4 days ago

malusrecord liked this · 4 days ago -

itsdegata-blog liked this · 4 days ago

itsdegata-blog liked this · 4 days ago -

vhagar-balerion-meraxes liked this · 4 days ago

vhagar-balerion-meraxes liked this · 4 days ago -

bouncehousedemons liked this · 5 days ago

bouncehousedemons liked this · 5 days ago -

heretherebebookdragons reblogged this · 5 days ago

heretherebebookdragons reblogged this · 5 days ago -

mihu-bm liked this · 5 days ago

mihu-bm liked this · 5 days ago -

agentbreedlove reblogged this · 5 days ago

agentbreedlove reblogged this · 5 days ago -

viperinae reblogged this · 5 days ago

viperinae reblogged this · 5 days ago -

mandrakebrew reblogged this · 5 days ago

mandrakebrew reblogged this · 5 days ago -

teilzeiteinhorn reblogged this · 5 days ago

teilzeiteinhorn reblogged this · 5 days ago -

milkywayrollercoaster liked this · 6 days ago

milkywayrollercoaster liked this · 6 days ago -

king-toad liked this · 6 days ago

king-toad liked this · 6 days ago -

shepfax liked this · 6 days ago

shepfax liked this · 6 days ago -

nightydraws liked this · 6 days ago

nightydraws liked this · 6 days ago -

serelius liked this · 6 days ago

serelius liked this · 6 days ago -

eunjung-chang reblogged this · 6 days ago

eunjung-chang reblogged this · 6 days ago -

incognito-insomniac reblogged this · 6 days ago

incognito-insomniac reblogged this · 6 days ago -

asmodevsa reblogged this · 1 week ago

asmodevsa reblogged this · 1 week ago -

elephantsnever4get reblogged this · 1 week ago

elephantsnever4get reblogged this · 1 week ago -

halfmoonshines reblogged this · 1 week ago

halfmoonshines reblogged this · 1 week ago -

dazeyeyes reblogged this · 1 week ago

dazeyeyes reblogged this · 1 week ago -

the-ghost-of-jason-todd liked this · 1 week ago

the-ghost-of-jason-todd liked this · 1 week ago -

mothhand reblogged this · 1 week ago

mothhand reblogged this · 1 week ago -

vieqo liked this · 1 week ago

vieqo liked this · 1 week ago -

faeriemelody reblogged this · 1 week ago

faeriemelody reblogged this · 1 week ago -

chroniclesofskye liked this · 1 week ago

chroniclesofskye liked this · 1 week ago -

theraddestartintown reblogged this · 1 week ago

theraddestartintown reblogged this · 1 week ago -

tranquilsatyr reblogged this · 1 week ago

tranquilsatyr reblogged this · 1 week ago -

zerobotic reblogged this · 1 week ago

zerobotic reblogged this · 1 week ago -

ravenrose27 liked this · 1 week ago

ravenrose27 liked this · 1 week ago -

georges-chambers reblogged this · 1 week ago

georges-chambers reblogged this · 1 week ago -

alienmythologist liked this · 1 week ago

alienmythologist liked this · 1 week ago -

morally-gayer liked this · 1 week ago

morally-gayer liked this · 1 week ago -

descisco reblogged this · 1 week ago

descisco reblogged this · 1 week ago -

freesoulpatrol reblogged this · 1 week ago

freesoulpatrol reblogged this · 1 week ago -

theverypulseofthemachine reblogged this · 1 week ago

theverypulseofthemachine reblogged this · 1 week ago -

artnachronisme reblogged this · 1 week ago

artnachronisme reblogged this · 1 week ago -

elvimoon reblogged this · 1 week ago

elvimoon reblogged this · 1 week ago -

maxiimoffwanda reblogged this · 1 week ago

maxiimoffwanda reblogged this · 1 week ago -

maxiimoffwanda liked this · 1 week ago

maxiimoffwanda liked this · 1 week ago -

alistairian reblogged this · 1 week ago

alistairian reblogged this · 1 week ago -

alistairian liked this · 1 week ago

alistairian liked this · 1 week ago -

riceeeeeeeeeew liked this · 1 week ago

riceeeeeeeeeew liked this · 1 week ago -

glinnmelethril reblogged this · 1 week ago

glinnmelethril reblogged this · 1 week ago -

glinnmelethril liked this · 1 week ago

glinnmelethril liked this · 1 week ago -

silviafwolfe reblogged this · 1 week ago

silviafwolfe reblogged this · 1 week ago