Striped Bark Maples Which Give Good All Season Interest And I Went On A Buying Spree 20-30 Years Ago.

Striped bark maples which give good all season interest and I went on a buying spree 20-30 years ago. Bark in general is really undervalued in gardens as a feature.

More Posts from Calystegia and Others

Ok but can we talk about non-native and invasive species in a nuanced way?

There’s more to this topic than ‘native = good’ and ‘non-native = invasive and therefore bad’. I also see horrible analogies with human immigration, which…no. Just no.

Let’s sit back and learn about species and how they work inside and outside their native ranges! Presented by: someone who studied ecology.

Broadly speaking, when talking about species in an ecosystem, we can divide them into four categories: native non-invasive, non-native, non-native invasive, and native invasive.

Because ‘native’ and ‘invasive’ are two different things.

Native and non-native refers to the natural range of a species: where it is found without human intervention. Is it there on its own, or did it arrive in a place because of human activity?

Non-invasive and invasive refers to how it interacts with its ecosystem. A non-invasive species slots in nicely. It has its niche, it is able to survive and thrive, and its presence does not threaten the ecosystem as a whole. An invasive species, on the other hand, survives, thrives, and threatens the balance of an ecosystem.

Let’s have some examples! (mostly featuring North America, because that’s the region I’m most familiar with)

Native Non-invasive

Native bees! Bee species (may be social or solitary) that pollinate plants.

And stopping here bc I think we get the point.

Non-native

Common Dandelion: Introduced from Europe. Considered an agricultural weed, but does no harm to the North American ecosystem. Used as a food source by many insects and animals. Is prolific, but does not force other species out.

European Honeybee: Introduced from Eurasia. Massively important insect for agricultural pollination. Can compete with native pollinators but does not usually out compete them.

Non-native Invasive

Emerald Ash Borer: Beetle introduced from Asia. In places where it is non-native, it is incredibly destructive to ash trees (in its native range, predators and resistant trees keep it in check). It threatens North America’s entire ash population.

Hydrilla: An Old World aquatic plant introduced to North America. Aggressively displaces native plant species, and can interfere with fish spawning areas and bird feeding areas.

Native Invasive

White Tailed Deer: Local extinction of the deer’s predators caused a massive population boom. Overgrazing by large deer populations has significantly changed the landscape, preventing forests from maturing and altering the species composition of an area. Regulated hunting keeps deer populations managed.

Sea Urchins: The fur trade nearly wiped out the sea otters that eat them. Without sea otters to keep urchin populations in check, sea urchins overgrazed on kelp forests, leading to the destruction and loss of kelp and habitat. Sea otter conservation has helped control urchin populations, and keeps the kelp forest habitat healthy.

—

There are a few common threads here:

The first is that human activities wind up causing most ecosystem damage. We introduce species. We disrupt food chains. We try to force human moral values onto ecosystems and species. And when we make a mistake, it’s up to us to mitigate or reverse the damage.

The second is that human moral values really cannot be applied to ecosystems. There are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ species. Every species has its place. Applying emotional and moral rhetoric to ecology works against our understanding of how our ecosystems work.

Third: the topic of invasive and non-native species is more complex than most of the dialogue surrounding it. Let’s elevate our discussions.

Fourth: If you ever compare immigrants or minorities to invasive species, I will end you.

There are more nuances to this topic than I presented as well! This is not meant to be a deep dive, but a primer.

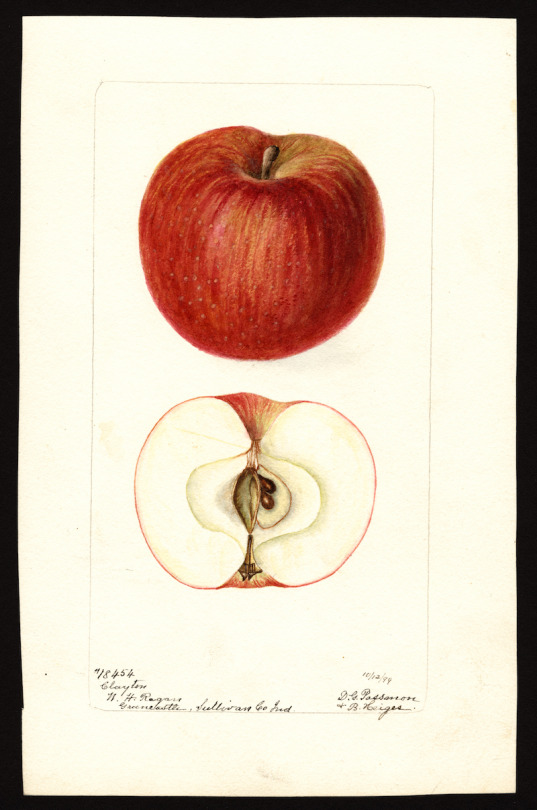

At what point does an exploration of these images tip from information into knowledge? It’s hard to say, but it’s unlikely we would pursue either one if that pursuit didn’t also include its share of pleasure. Enter the USDA’s Pomological Watercolor Collection here to [view] and download over 7,500 high-resolution digital images like those above.

I wonder how many of these fruits & vegetables have changed since 1886?

Invasive Species and Xenophobia

Invasive species are complicated! People have a lot of feelings about them, positive and negative. Are plants that move "invaders" "colonizing", "immigrants", "citizens"? What does it mean to kill species that are from somewhere else? What if that species legitimately makes a poor neighbor and causes extinctions in other, native species? This complex, culturally-loaded issue is a foundational issue behind a lot of plant conservation and restoration.

This is a juicy and still actively disputed topic! The Guardian recently had a big article on colonialism in Botany, (tbh her views are dated and reductive, imo) and it’s come up again this week, to much hostility (cw: reddit). Yes, my region's native plant restoration came from literal nazis, but also, the impacts of some invasive species are real, not figments of a racist imagination. How do we balance these issues? What does ethical invasive management look like?

Since it’s such a juicy topic, I wanted to offer a few fun readings to share:

The Native Plant Enthusiasm: Ecological Panacea or Xenophobia?, Gert Gröning and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn, 2004, Arnoldia.

THE CLASSIC 20th century German nazis and native plants paper. Made a huge splash when it came out, and you will still encounter people who paint all native plant stuff with this brush. Summary: yeah the nazis loved their native plants and used them as part of their conquering process. Also, the first prairie plantings ever, located in Chicago, were done by a racist probable-nazi for racist reasons, full stop. I’ll let him speak for himself: “The gardens that I created myself shall… be in harmony with their landscape environment and the racial characteristics of its inhabitants. They shall express the spirit of America and therefore shall be free of foreign character as far as possible… the Latin and the Oriental crept and creeps more and more over our land, coming from the South, which is settled by Latin people, and also from other centers of mixed masses of immigrants. The Germanic character of our race, of our cities and settlements was overgrown by foreign character. The Latin spirit has spoiled a lot and still spoils things every day.” - Jens Jensen

Botanical decolonization: rethinking native plants, Tomaz Mastnak, 2014, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space

Rather than viewing native plant plantings as an act of racially-pure occupation, Mastnak positions native plants in California as a decolonization of the sub/urban lawn. Uses a lot of quotations from 16th century English philosopher Francis Bacon, and is heavy on the philosophical musings.

From killing lists to healthy country: Aboriginal approaches to weed control in the Kimberley, Western Australia by Bach et al., 2019, Journal of Environmental Management.

This paper talks through some of the native vs invasive debate, and offers a different perspective on how to approach to plant invasive management based on cultural relations, rather than country of origin or behavior.

Beyond ‘Native V. Alien’: Critiques of the Native/alien Paradigm in the Anthropocene, and Their Implications, Charles R. Warren, 2021, Ethics, Policy, & Environment

DENSE but thorough, if you want to follow the entire history of the native/invasive debate, this has you covered. The most interesting stuff, in my opinion, is the discussion of invasive denialism, IE: the impasse of “You’re just being racist!” Vs “You know nothing about ecology!” I recommend the Discussion, which starts on page 13.

White Calla

-

pccyouthleader liked this · 3 months ago

pccyouthleader liked this · 3 months ago -

tangledlichen reblogged this · 3 months ago

tangledlichen reblogged this · 3 months ago -

tangledlichen liked this · 3 months ago

tangledlichen liked this · 3 months ago -

athos-silvani liked this · 3 months ago

athos-silvani liked this · 3 months ago -

neezieneezie reblogged this · 3 months ago

neezieneezie reblogged this · 3 months ago -

artificial-condition liked this · 3 months ago

artificial-condition liked this · 3 months ago -

rederiswrites reblogged this · 3 months ago

rederiswrites reblogged this · 3 months ago -

monardammm reblogged this · 3 months ago

monardammm reblogged this · 3 months ago -

monardammm liked this · 3 months ago

monardammm liked this · 3 months ago -

irgum-burgum liked this · 3 months ago

irgum-burgum liked this · 3 months ago -

parrot-parent liked this · 3 months ago

parrot-parent liked this · 3 months ago -

naalbinder liked this · 3 months ago

naalbinder liked this · 3 months ago -

aabcdp reblogged this · 3 months ago

aabcdp reblogged this · 3 months ago -

aabcdp liked this · 3 months ago

aabcdp liked this · 3 months ago -

ideasthatwillneverbepublished liked this · 3 months ago

ideasthatwillneverbepublished liked this · 3 months ago -

thefortressofarebelsoul liked this · 3 months ago

thefortressofarebelsoul liked this · 3 months ago -

goneahead liked this · 3 months ago

goneahead liked this · 3 months ago -

late-in-the-day liked this · 3 months ago

late-in-the-day liked this · 3 months ago -

pig-wings liked this · 3 months ago

pig-wings liked this · 3 months ago -

figure8track liked this · 3 months ago

figure8track liked this · 3 months ago -

figure8track reblogged this · 3 months ago

figure8track reblogged this · 3 months ago -

regenerationsfarm liked this · 3 months ago

regenerationsfarm liked this · 3 months ago -

5-and-a-half-acres reblogged this · 3 months ago

5-and-a-half-acres reblogged this · 3 months ago -

dinosnaurs reblogged this · 4 months ago

dinosnaurs reblogged this · 4 months ago -

calystegia reblogged this · 4 months ago

calystegia reblogged this · 4 months ago -

gloomierdays reblogged this · 5 months ago

gloomierdays reblogged this · 5 months ago -

thebigjawpokemon reblogged this · 6 months ago

thebigjawpokemon reblogged this · 6 months ago -

shockingheaven reblogged this · 6 months ago

shockingheaven reblogged this · 6 months ago -

juno-stuffs liked this · 7 months ago

juno-stuffs liked this · 7 months ago -

joycelikesflowers reblogged this · 7 months ago

joycelikesflowers reblogged this · 7 months ago -

zeroand1 liked this · 7 months ago

zeroand1 liked this · 7 months ago -

themischiefoftad liked this · 7 months ago

themischiefoftad liked this · 7 months ago -

adelphicoracle liked this · 7 months ago

adelphicoracle liked this · 7 months ago -

saidthesparrowtothedove reblogged this · 7 months ago

saidthesparrowtothedove reblogged this · 7 months ago -

gelana78 liked this · 7 months ago

gelana78 liked this · 7 months ago -

deadsearisen liked this · 7 months ago

deadsearisen liked this · 7 months ago -

clovercollector liked this · 7 months ago

clovercollector liked this · 7 months ago -

tennyo-elf liked this · 7 months ago

tennyo-elf liked this · 7 months ago -

dinosnaurs liked this · 7 months ago

dinosnaurs liked this · 7 months ago -

opal-bee liked this · 7 months ago

opal-bee liked this · 7 months ago -

asthoughtobreathewerelife liked this · 7 months ago

asthoughtobreathewerelife liked this · 7 months ago -

rederiswrites reblogged this · 7 months ago

rederiswrites reblogged this · 7 months ago -

rederiswrites liked this · 7 months ago

rederiswrites liked this · 7 months ago -

proteusolm liked this · 7 months ago

proteusolm liked this · 7 months ago -

twofistfuls liked this · 7 months ago

twofistfuls liked this · 7 months ago -

enrejts liked this · 7 months ago

enrejts liked this · 7 months ago -

bee-unknown liked this · 7 months ago

bee-unknown liked this · 7 months ago -

rmelster reblogged this · 7 months ago

rmelster reblogged this · 7 months ago

icon: Cressida Campbell"I know the human being and fish can co-exist peacefully."

35 posts