Invasive Species And Xenophobia

Invasive Species and Xenophobia

Invasive species are complicated! People have a lot of feelings about them, positive and negative. Are plants that move "invaders" "colonizing", "immigrants", "citizens"? What does it mean to kill species that are from somewhere else? What if that species legitimately makes a poor neighbor and causes extinctions in other, native species? This complex, culturally-loaded issue is a foundational issue behind a lot of plant conservation and restoration.

This is a juicy and still actively disputed topic! The Guardian recently had a big article on colonialism in Botany, (tbh her views are dated and reductive, imo) and it’s come up again this week, to much hostility (cw: reddit). Yes, my region's native plant restoration came from literal nazis, but also, the impacts of some invasive species are real, not figments of a racist imagination. How do we balance these issues? What does ethical invasive management look like?

Since it’s such a juicy topic, I wanted to offer a few fun readings to share:

The Native Plant Enthusiasm: Ecological Panacea or Xenophobia?, Gert Gröning and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn, 2004, Arnoldia.

THE CLASSIC 20th century German nazis and native plants paper. Made a huge splash when it came out, and you will still encounter people who paint all native plant stuff with this brush. Summary: yeah the nazis loved their native plants and used them as part of their conquering process. Also, the first prairie plantings ever, located in Chicago, were done by a racist probable-nazi for racist reasons, full stop. I’ll let him speak for himself: “The gardens that I created myself shall… be in harmony with their landscape environment and the racial characteristics of its inhabitants. They shall express the spirit of America and therefore shall be free of foreign character as far as possible… the Latin and the Oriental crept and creeps more and more over our land, coming from the South, which is settled by Latin people, and also from other centers of mixed masses of immigrants. The Germanic character of our race, of our cities and settlements was overgrown by foreign character. The Latin spirit has spoiled a lot and still spoils things every day.” - Jens Jensen

Botanical decolonization: rethinking native plants, Tomaz Mastnak, 2014, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space

Rather than viewing native plant plantings as an act of racially-pure occupation, Mastnak positions native plants in California as a decolonization of the sub/urban lawn. Uses a lot of quotations from 16th century English philosopher Francis Bacon, and is heavy on the philosophical musings.

From killing lists to healthy country: Aboriginal approaches to weed control in the Kimberley, Western Australia by Bach et al., 2019, Journal of Environmental Management.

This paper talks through some of the native vs invasive debate, and offers a different perspective on how to approach to plant invasive management based on cultural relations, rather than country of origin or behavior.

Beyond ‘Native V. Alien’: Critiques of the Native/alien Paradigm in the Anthropocene, and Their Implications, Charles R. Warren, 2021, Ethics, Policy, & Environment

DENSE but thorough, if you want to follow the entire history of the native/invasive debate, this has you covered. The most interesting stuff, in my opinion, is the discussion of invasive denialism, IE: the impasse of “You’re just being racist!” Vs “You know nothing about ecology!” I recommend the Discussion, which starts on page 13.

More Posts from Calystegia and Others

Ragwort

White Calla

Some of you may have heard about Monarch butterflies being added to the Threatened species list in the US and be planning to immediately rush out in spring and buy all the milkweed you can manage to do your part and help the species.

And that's fantastic!! Starting a pollinator garden and/or encouraging people and businesses around you to do the same is an excellent way to help not just Monarchs but many other threatened and at-risk pollinator species!

However.

Please please PLEASE do not obtain Tropical Milkweed for this purpose!

Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica)--also commonly known as bloodflower, Mexican butterflyweed, and scarlet milkweed--will likely be the first species of milkweed you find for sale at most nurseries. It'll be fairly cheap, too, and it grows and propagates so easily you'll just want to grab it! But do not do that!

Tropical milkweed can cause a host of issues that can ultimately harm the butterflies you're trying to help, such as--

Harboring a protozoan parasite called OE (which has been linked to lower migration success, reductions in body mass, lifespan, mating success, and flight ability) for long periods of time

Remaining alive for longer periods, encouraging breeding during migration time/overwintering time as well as keeping monarchs in an area until a hard freeze wherein which they die

Actually becoming toxic to monarch caterpillars when exposed to warmer temperatures associated with climate change

However--do not be discouraged!! There are over 100 species of milkweed native to the United States, and plenty of resources on which are native to your state specifically! From there, you can find the nurseries dedicated to selling native milkweeds, or buy/trade for/collect seeds to grow them yourself!!

The world of native milkweeds is vast and enchanting, and I'm sure you'll soon find a favorite species native to your area that suits your growing space! There's tons of amazing options--whether you choose the beautiful pink vanilla-smelling swamp milkweed, the sophisticated redring milkweed, the elusive purple milkweed, the alluring green antelopehorn milkweed, or the charming heartleaf milkweed, or even something I didn't list!

And there's tons of resources and lots of people willing to help you on your native milkweed journey! Like me! Feel free to shoot me an ask if you have any questions!

Just. PLEASE. Leave the tropical milkweed alone. Stay away.

TLDR: Start a pollinator garden to help the monarchs! Just don't plant tropical milkweed. There's hundreds of other milkweeds to grow instead!

“Pitcher Plant”

I dislike the term “pitcher plant”. It reeks of outdated ignorance and describes a vast number of species from around the world, many of which are not closely related to each other.

As a botanist, and an evil one at that, I prefer to be precise with my language. You too can become an educated scientist and terrific snob by using the correct terms for each variety of “pitcher plant”. If you require education on the matter, allow me to inform you.

There are three families of “pitcher plant”: Sarraceniaceae, Nepenthaceae, and Cephalotaceae. Sarraceniaceae has 3 genera — namely Sarracenia, Heliamphora, and Darlingtonia. Nepenthaceae has a single genus (Nepenthes), and Cephalotaceae has a single species. An entire family with only one species. Ugh.

Now, they look quite distinct from each other, so here are some photos and facts.

This species belongs to Sarracenia, the North American or trumpet pitcher plants. Note the height and slender shape.

This is also a Sarracenia. Note the lack of height and squat shape. Most Sarracenia species look like one of these two — they are quite easy to identify. They are found in boggy, temperate areas around North America and reach a height of up to 4 feet tall.

This is a stunning example of a Nepenthes (tropical pitcher plants) species. These are what you likely think of when someone mentions “pitcher plants”. Beautiful, found in warm, humid regions of the world. They are climbing vines and pitchers can reach over a foot tall (this is species-dependent).

This is an example of Heliamphora, the sun pitchers. They can be found in South America. While still belonging to the family Sarraceniaceae, they are not as tall as Sarracenia, but still quite graceful. If you have a mind for Greek, you may wonder if the “heli” in Heliamphora is for sun (from “helios”). It is not. The name Heliamphora instead comes from “helos”, meaning marsh. The name “sun pitcher” is misleading and comes from a misunderstanding — these plants would be more accurately called “marsh pitchers”.

I have a passionate love-hate relationship with Cephalotus follicularis. Cephalotus is a monotypic genus (a genus with only one species) and of course it is Australian. They look similar to Nepenthes but are unrelated and much smaller — the plants reach just shy of 8 inches tall.

There are also the cobra lilies, Darlingtonia, which belong to Sarraceniaceae. Those are arguably similar enough to Sarracenia that they do not need to be discussed here. Darlingtonia is another monotypic genus within Sarraceniaceae.

Now you have absolutely no excuse. You have been informed on the major genera of “pitcher plants” and should weaponize this knowledge as you see fit.

The brilliant and brave may also wish to weaponize the plants themselves. Kindly send me updates if you do. I am ever so curious…

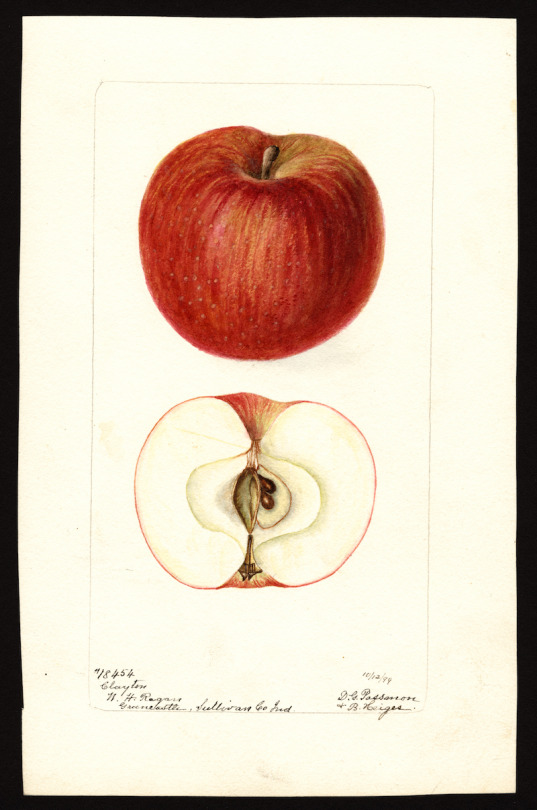

At what point does an exploration of these images tip from information into knowledge? It’s hard to say, but it’s unlikely we would pursue either one if that pursuit didn’t also include its share of pleasure. Enter the USDA’s Pomological Watercolor Collection here to [view] and download over 7,500 high-resolution digital images like those above.

I wonder how many of these fruits & vegetables have changed since 1886?

FINALLY the buttonbush pictures. These are just about the coolest flowers in the world. And they grow all over the riverbanks and are swarmed with pollinators right now it’s amazing. My mom and I couldn’t canoe 10 feet without spotting another one and of course we couldn’t not check out every single one.

Erica pyramidalis, the pyramid heath, was a species of Erica (also sometimes known as heath/heather) that was endemic to the city of Cape Town, South Africa. Erica is a genus of roughly 857 species of flowering plants in the family Ericaceae. The Pyramid Heath was restricted to what today is the city of Cape Town in the Western Cape Province, South Africa.The species disappeared due to the destruction of its habitat by the expanding city, and, despite the fact that the species was even cultivated for some time it is now considered extinct.

Mystical Rock Lotus

An extraordinary plant with delicate pink blossoms emerging from rugged rocks, supported by intricate and vibrant pink roots that cascade down the stone surfaces, creating a mesmerizing display of natures resilience and beauty!

Light: Partial to full sunlight.

Water: Mist regularly to maintain moisture around the roots.

Soil: Requires minimal substrate, often growing directly on rocks.

Temp: 60-75F 16-24C.

Humidity: High humidity is essential.

Fertilizer: Rarely needed; thrives in natural, nutrient-rich environments.

This plant is perfect for creating a unique and captivating focal point in rock gardens or terrariums!

source: Coffee loves

-

goofycunt reblogged this · 1 month ago

goofycunt reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ethernetmeep liked this · 1 month ago

ethernetmeep liked this · 1 month ago -

feverish-hell liked this · 1 month ago

feverish-hell liked this · 1 month ago -

watchfuldeer liked this · 1 month ago

watchfuldeer liked this · 1 month ago -

i-am-a-dragon-dragon reblogged this · 1 month ago

i-am-a-dragon-dragon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

i-am-a-dragon-dragon liked this · 1 month ago

i-am-a-dragon-dragon liked this · 1 month ago -

possumwoodpie reblogged this · 1 month ago

possumwoodpie reblogged this · 1 month ago -

randaness reblogged this · 1 month ago

randaness reblogged this · 1 month ago -

arosarrowseros liked this · 1 month ago

arosarrowseros liked this · 1 month ago -

662607015 liked this · 1 month ago

662607015 liked this · 1 month ago -

homeplanets reblogged this · 1 month ago

homeplanets reblogged this · 1 month ago -

yami268 liked this · 2 months ago

yami268 liked this · 2 months ago -

yincira reblogged this · 2 months ago

yincira reblogged this · 2 months ago -

topazera liked this · 2 months ago

topazera liked this · 2 months ago -

angfdz reblogged this · 2 months ago

angfdz reblogged this · 2 months ago -

elfiepike reblogged this · 2 months ago

elfiepike reblogged this · 2 months ago -

girlouse reblogged this · 2 months ago

girlouse reblogged this · 2 months ago -

the-name-was-lost reblogged this · 2 months ago

the-name-was-lost reblogged this · 2 months ago -

deltragon reblogged this · 2 months ago

deltragon reblogged this · 2 months ago -

dahliavandare liked this · 2 months ago

dahliavandare liked this · 2 months ago -

flyingbodysymphony liked this · 2 months ago

flyingbodysymphony liked this · 2 months ago -

meh-66 reblogged this · 2 months ago

meh-66 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

meh-66 liked this · 2 months ago

meh-66 liked this · 2 months ago -

weirdoughnut reblogged this · 2 months ago

weirdoughnut reblogged this · 2 months ago -

holdingstack reblogged this · 2 months ago

holdingstack reblogged this · 2 months ago -

garymerlow reblogged this · 2 months ago

garymerlow reblogged this · 2 months ago -

garymerlow liked this · 2 months ago

garymerlow liked this · 2 months ago -

labelleizzy reblogged this · 2 months ago

labelleizzy reblogged this · 2 months ago -

labelleizzy liked this · 2 months ago

labelleizzy liked this · 2 months ago -

humanradiohead reblogged this · 2 months ago

humanradiohead reblogged this · 2 months ago -

rileyram12 liked this · 2 months ago

rileyram12 liked this · 2 months ago -

costcodog reblogged this · 2 months ago

costcodog reblogged this · 2 months ago -

misfitmagpie reblogged this · 3 months ago

misfitmagpie reblogged this · 3 months ago -

clever-but-devastating liked this · 3 months ago

clever-but-devastating liked this · 3 months ago -

malicious-compliance-esq reblogged this · 3 months ago

malicious-compliance-esq reblogged this · 3 months ago -

malicious-compliance-esq liked this · 3 months ago

malicious-compliance-esq liked this · 3 months ago -

untitledgoosegay reblogged this · 3 months ago

untitledgoosegay reblogged this · 3 months ago -

bisonposting reblogged this · 3 months ago

bisonposting reblogged this · 3 months ago -

nentuaby reblogged this · 3 months ago

nentuaby reblogged this · 3 months ago -

carvois-tu liked this · 3 months ago

carvois-tu liked this · 3 months ago -

samfparker liked this · 3 months ago

samfparker liked this · 3 months ago -

samfparker reblogged this · 3 months ago

samfparker reblogged this · 3 months ago -

countingnothings reblogged this · 3 months ago

countingnothings reblogged this · 3 months ago -

the-whale-institute liked this · 3 months ago

the-whale-institute liked this · 3 months ago -

letheancloud liked this · 3 months ago

letheancloud liked this · 3 months ago -

transmechanicus liked this · 3 months ago

transmechanicus liked this · 3 months ago -

ghostlyraptor liked this · 3 months ago

ghostlyraptor liked this · 3 months ago -

darlingsweetprince liked this · 3 months ago

darlingsweetprince liked this · 3 months ago -

thepowerfulplay17 reblogged this · 3 months ago

thepowerfulplay17 reblogged this · 3 months ago -

spontaneousglitterbees liked this · 3 months ago

spontaneousglitterbees liked this · 3 months ago

icon: Cressida Campbell"I know the human being and fish can co-exist peacefully."

35 posts